My Etsy shop for ordering photo prints is now open. It features hundreds of my favorite photos available as archival giclée prints that will last for generations.

Canon F-1, the Root of Canon’s Pro Line

I found an original Canon F-1 at a yard sale a couple of years ago by surprise. It was right in the prime of yard sale season and I was in pursuit of old magazines. I sell vintage ads (VintageVirtus on Etsy) and saw a Craigslist ad for “old magazines.” Milling around with a meager $60 in my pocket, I noticed a box with camera lenses sticking out. I slithered over to it, not wanting to look too excited and revealing that my heart had skipped a beat and my palms were starting to sweat. I reached into the 24-bottles-of-beer-sized cardboard box and started rummaging around. I was alone at this point, because this was a very large “living estate” sale spread out in the backyard of a modest ranch-style house. Everyone else was interested in fishing poles, kitchen ware, and lawn tools. One of the first things I noticed was a massive Soligor 500mm mirror lens. Hmmm…I already have one of these in a Canon FD mount…looks like this one is for Canon as well. There were a number of cameras, lenses, flashes, cases, and other accessories, and a large motor drive attachment. It said “Canon” on it and was heavy. I set it aside and plucked deeper, past a Minolta XG and a few point-and-shoots, to find the holy grail – a Canon F-1.

The camera had a zoom lens on it and seemed to be in decent shape, though dusty. I have always kept my eye out for an F-1 at yard sales and flea markets, but have never run across one. Plenty of AE-1s, a few A-1s and FTs, but never anything in this class at a yard sale. Just about then, a guy chewing on a cigar saw me digging in the gold mine and said, “Make me an offer. I want to get rid of everything.”

There were maybe 25 items in the box – an assortment of lenses, mostly Canons I already had and several off-brands, a Minolta SLR and lenses, point-and-shoots, a few flashes, and cases – nothing else I really wanted to keep or take the effort to sell. Not wanting to offend him by only offering $60 (what was in my pocket) for a whole box easily worth $300 in resale value, I asked if he would be willing to sell just a few items. “Sure!” he replied. So I hastily found a 50mm 1.4 lens, sloppily screwed the motor drive to the bottom of the F-1, and said, “How much for the Canon?”

He looked at me a moment and asked what lens I had there. “The standard 50,” I replied. The 50/1.4 is by no means “standard” in my book. It has great contrast, bokeh, speed, and sharpness. He paused a moment, took a puff on his cigar, and said, “$60.”

“Sold!” I cried out, not believing my stroke of luck that day. I should have gone to the track! I wound up hanging around a while to find out the history of the camera and how he used it. He bought it second-hand from a friend that barely used it. He liked to photograph his Navy ship models. He was in the Navy for years, and took up building small, accurate models of ships. He must have had 200 in display cases for sale. We talked a bit about his model building and Navy days, and then he asked my advice for better lighting of his models. I truly enjoyed my time with the former owner of my camera, but I couldn’t wait to get home and try out my new find.

I did an initial cleanup of the surface, fully expecting a layer of grime and pockets of ashes from his stogie. The first good sign was that it was surprisingly clean. The inside was pristine, save for the failing light seals. I checked all functions, and was happy to see that everything worked. I checked online to see exactly what model I had, because I’ve always been confused about the F-1 lineup. After research, I determined I had the very first F-1 model that Canon made, approximately 1971. Not a bad thing, but I was hoping for the more modern New F-1 from the 1980s.

I stuck a standard SR-44 button battery in it to see if the meter worked. It sprung to life…another good sign. I next loaded what seemed like a carload of batteries into the motor drive. After correctly attaching it to the bottom, it also sprung to life and whirred as I pressed the shutter. So far everything was looking great. I put some exposed test film in, and it advanced effortlessly. Wow, this was a nice camera and in great shape – and it was 45 years old.

In fact, after using this camera for a few years, I’ve found it to still operate like new. There’s some minor brassing (not always a bad thing), and someone has adjusted the meter (either mechanically or electronically using a diode) to take modern 1.55V batteries.

Many cameras from this timeline use the now-outlawed 1.35V mercury batteries. Modern users have several choices, from ignoring the higher readings a 1.55V battery gives, to adapting 1.35V hearing aid batteries, to modifying the camera’s electronics to take modern batteries. I choose to either a) use a handheld meter, b) use hearing aid batteries with an adapter, or c) modify the electronics with a diode. Each vintage camera requires a different decision.

I have fallen in love with this camera. I had often pulled out my Canon FTBn when I was feeling nostalgic. The FTBn is very similar, but is a consumer model. It has a solid build, accurate meter, and just feels good in the hands. (Read this great article that profiles the FTb and F-1). My love for the FD line of lenses has driven me to acquire several older Canon cameras to shoot with. I landed an A-1 about 10 years ago and tried to love it. I was enamored with the controls and layout, but couldn’t get past the clunky manual metering mode. I stumbled across an AE-1 and actually enjoyed shooting with it more than the A-1. I then found a T-90, which I found almost exciting. I love its multi-spot metering mode, which is similar to the dead-simple Olympus OM-4. But again, I found it a little clunky. I have to remind myself that these cameras came out in the 70s and 80s and were light years ahead of their competitors.

I am a mostly manual setting shooter, occasionally switching to aperture priority if I can lock exposure. I looked at the Canon AV-1 but was scared off by its consumer-oriented build. And then the F-1 entered my world. I think the combined pro-level build, the weight, and the ergonomics have won me over. I started my semi-pro career in the 1970s with a Minolta SRT-101, so grabbing metal dials on the top of the camera, twisting rings around the lens, and pushing a mechanical shutter button come naturally for me. Plus, the dead-on meter gives me confidence when out in the field without a handheld meter.

I am a mostly manual setting shooter, occasionally switching to aperture priority if I can lock exposure. I looked at the Canon AV-1 but was scared off by its consumer-oriented build. And then the F-1 entered my world. I think the combined pro-level build, the weight, and the ergonomics have won me over. I started my semi-pro career in the 1970s with a Minolta SRT-101, so grabbing metal dials on the top of the camera, twisting rings around the lens, and pushing a mechanical shutter button come naturally for me. Plus, the dead-on meter gives me confidence when out in the field without a handheld meter.

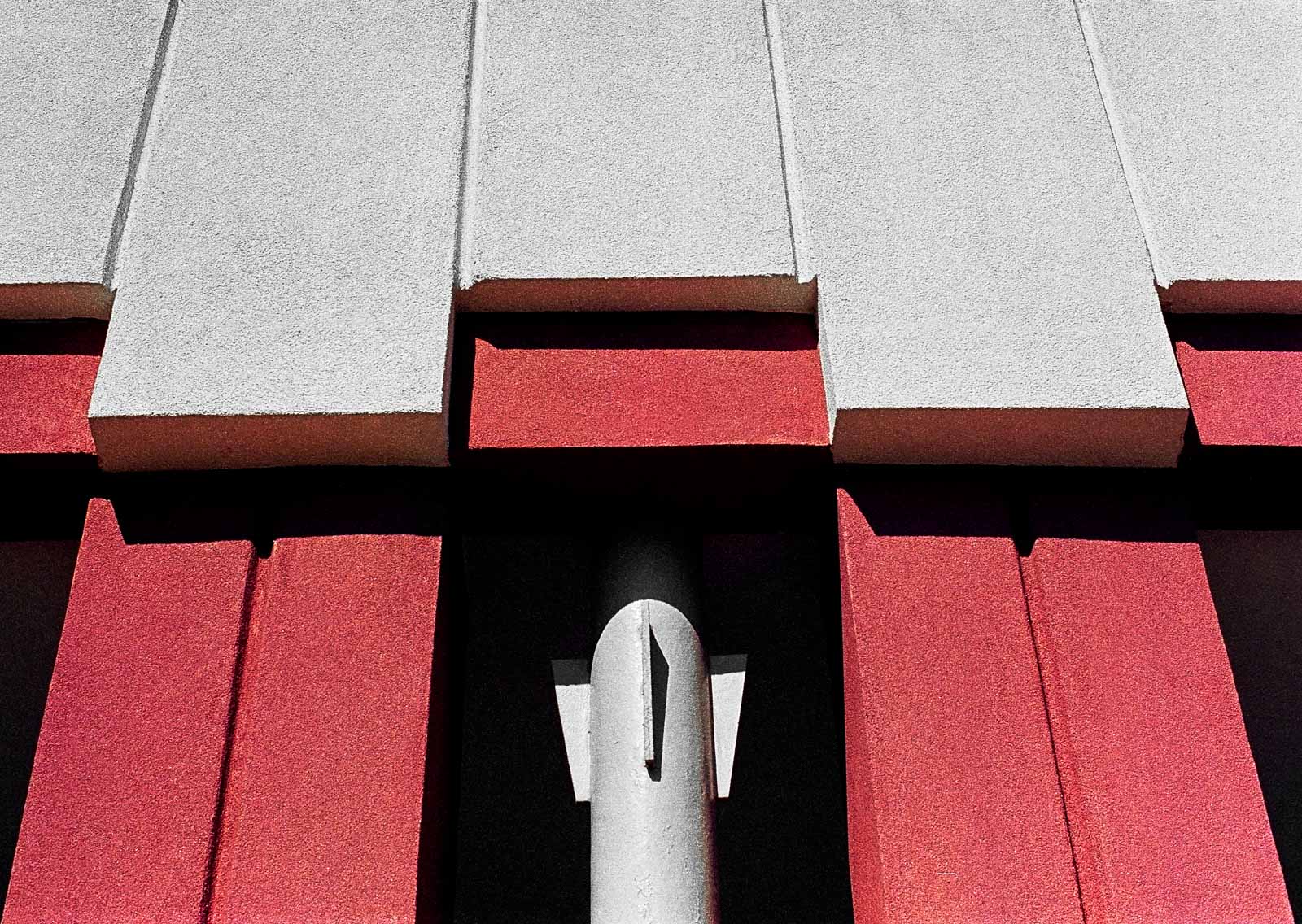

Central Support (Canon F-1, Kodak Portra 400)

The motor drive (Motor Drive F) is competent, but pretty heavy for my style of shooting. The finder is pretty good, but I have a little trouble focusing. I’ll have to seek out a diopter or newer split-prism finder. The film advance is solid and smooth. It has mirror lock-up for long exposures. Mine has the Flash Coupler F, which essentially puts a regular hot shoe over the prism like most later cameras. The F-1 had that awkward rewind-side-mounted flash contact similar to the Nikon F, F2, and F3, so this is a welcome addition when I use a flash.

The camera by itself is a little heavy, but I don’t mind that. I prefer some weight to help in steadying my slow shutter shots. That sounds silly, but if a camera is too lightweight, your shaky arms and hands are telegraphed to the camera. A little weight seems to dampen the small movements that ruin photos. Of course too heavy and your arms shake, so this is a good balance. I have to be careful when laying it down, as it may dent the surface I’m setting it on. Lay it down slowly and softly. Don’t worry about the camera, it’s a tank.

Jasper (Canon F-1, Kodak Ektar 100)

The match-needle meter is dead-on accurate. It takes a little getting used to though. You don’t see the needle if the light is too low and your speed or aperture are set too high. Don’t panic, adjust the speed and/or aperture until it pops into view on the bottom. The only light the viewfinder gets is natural light via a little translucent window on the top left of the body. They made a light accessory (and about a thousand other accessories) for low light situations. The only other information you get is the speed, again lit by that little window.

This is a fully manual camera, which is fine for me. I’ll take advantage of aperture-priority when it’s available, but my basic shooting style is full manual. I prefer to have a built-in meter when shooting 35mm, my speed control on top, and my aperture control around the ring. It’s how I learned, and the F-1 fits. When I’m shooting an unusual vintage camera, like my Zeiss-Ikon Contaflex, a Voigtlander Vitessa, or even my Olympus OM-1,2,4, I have to think for a split second about where the settings are. Not so with the F-1. This may be why Canon stuck with familiar industry standards for their pro line.

Which brings me to why this camera is interesting to me. This is Canon’s first attempt at a pro-level camera. This is before the T-90, the EOS-1V and the EOS-1D. It was Canon’s answer to the Nikon F and F2. It has one of the most comprehensive lineup of accessories ever produced for a 35mm camera. And being pro-level, you get solid build, exchangeable prisms and focus screens, different motor drives and power options, databacks, flashes, lenses, and the list goes on. If I take care of it, I feel like this camera will still be performing 45 years from now. And with the love this cameras gives back to me, I’m not sorry this isn’t a New F-1. Because this is the wise old granddaddy of them all.

Here are some pictures from this great camera, all on FD lenses.

Vitessa Impressa

I picked up a bucket list camera on the bay a few summers ago – a Voigtländer Vitessa N2. It’s a folding post-war 35mm rangefinder camera produced during the 1950s – the golden age of rangefinders. While it’s not the exact one on the bucket list, it’s close enough to get the full experience. The minor differences are its lens, which is a little slower than the cream of the crop, and that it has no meter. But the sheer cleverness and unique operation of the Vitessa make for a fun experience.

For those of you that know my camera collecting experiences, you know I love Voigtländers. These German-made gems were not necessarily the most coveted cameras to come out of Germany in the 1950s or 60s, but they might be considered the most accessible in terms of quality vs price. Leica, Exakta, Franke & Heidecke (Rolleiflex), and others were churning out high-priced cameras, many of them used professionally. They are highly collectible and still command high dollars today.

Inspiration

After the big war, photographic technology and technique started to rapidly evolve. Printers produced higher resolution books and magazines, cinema provided bigger screens and better projection, and photographers had finally been accepted into the world of art. The public’s expectations of seeing better photographs fed their desire to make better ones themselves. They expected better cameras, lenses, films, and papers. The Germans and Japanese answered (let’s not forget the French and Italians, too).

Professional photographers’ demands were always changing, and several manufacturers catered almost exclusively to them. But some camera makers were more interested in selling to the mass markets, like Zeiss-Ikon and Voigtländer. Though they both offered pro and semi-pro cameras, most were tailored to casual or serious amateurs. Fujifilm, Pentax, or Olympus would be modern day equivalents. Then, as now, they wanted their users to have a quality experience while producing superb pictures. They also wanted their cameras to last (a concept almost unheard of today).

Zeiss-Ikon and Voigtländer cameras from the 50s and 60s have stood the test of time. Many German cameras from the mid-century still work flawlessly. The build quality is above what anybody else was doing at the time. I don’t think it was necessarily a marketing ploy to build at this high level, after all they could sell more cameras with planned obsolescence. I think it was just the way they did things. They weren’t about to compromise the century-old sterling reputation for building precision mechanical cameras and timepieces.

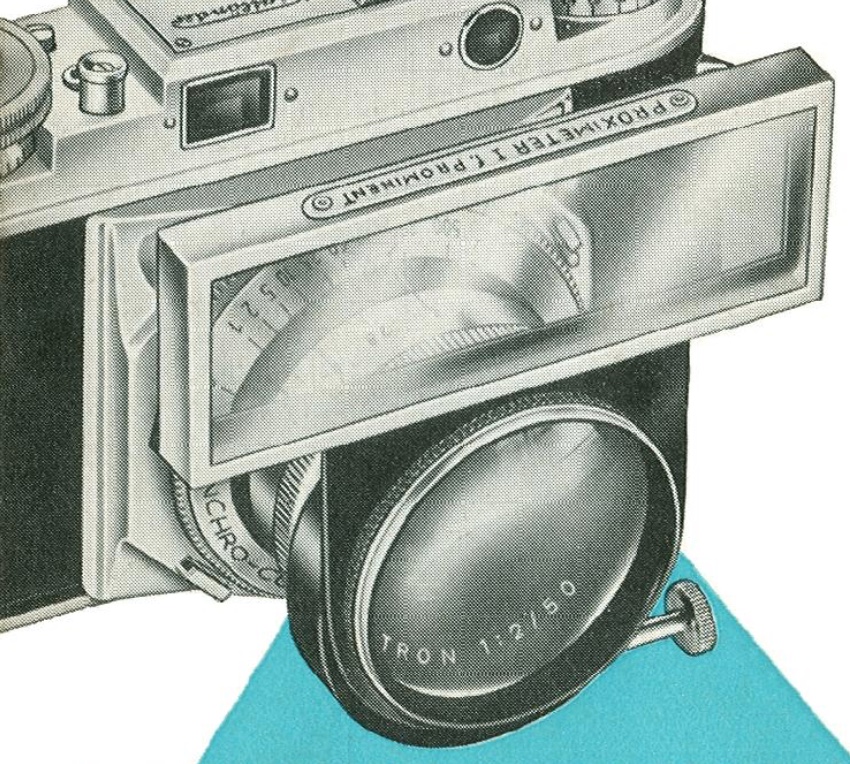

If you look through catalogs and magazines from this era, the German cameras were some of the most expensive for sure, but they also had a host of ingenious designs and accessories. But they would sometimes paint themselves into a corner with their clever designs. For instance, many rangefinders from the 1950’s suffered from parallax. Because you are viewing the scene above and to the left of the lens, closeups are impossible to frame. Camera makers limited focus to about 3 feet to prevent this error. To correct for parallax, some rangefinder viewers’ frame lines moved during focusing to indicate the approximate final frame.

Making the Complicated More Complicated

Other attempts were much more involved. Enter the “proximeter,” a fancy-sounding name for an over-engineered device. Because amateurs were mostly using these cameras, many wanted closeups of children, pets, and perhaps their prize rose. They had already spent a month or two’s wages on this camera, and they didn’t want to buy another one. The solution was a multiple-piece device that included a closeup filter for the lens, and a closeup filter for the viewfinder. This was attached in a variety of ways, usually involving movable rods, screws, wing nuts, and chains. I couldn’t attach the first one I owned without repeatedly referring to the instructions. With it on the camera, it looks more like a military device for spotting enemy planes than a solution to capturing Johnny’s smile. But it performed beautifully.

You have to remember that single lens reflexes (SLRs) were not yet common in the 1950’s, so camera engineers were just adding to the existing camera structure. With some of the attachments, these cameras started to resemble a Rube Goldberg machine. They were wonderfully overly complicated and exhibited clever problem-solving engineering.

You have to remember that single lens reflexes (SLRs) were not yet common in the 1950’s, so camera engineers were just adding to the existing camera structure. With some of the attachments, these cameras started to resemble a Rube Goldberg machine. They were wonderfully overly complicated and exhibited clever problem-solving engineering.

Making the Very Complicated Even More Complicated

Rangefinder focusing, parallax error, proximeter attachments – can they complicate things further? Of course! Enter: the Light Value System, or LVS. In the words of Roger Hicks, this “poisonous” system was neither useable nor understandable by amateurs. Just imagine if all of our textbooks and newspapers were all of a sudden written in Esperanto. A clean and logical language for those who speak it, but useless to the masses.

LVS was created to solve a few problems, namely the uncoupled light meter. The mad scientists that cooked up LVS reasoned that amateurs didn’t understand the relationships between f-stops and speeds. Users would rather deal with only one number. Read the number from the meter, then set the camera dial to that same number. Speed and aperture moved together. That in itself was brilliant. But in practice, one had to unlock one or the other to be creative. The Vitessa has this “feature” and is difficult to release, though not as difficult as others, such as Kodak Retina folders.

Making the Really Complicated Very Simple – and Quirky

When I first saw a Vitessa in a picture, I noticed that weird rod sticking up on top of the camera body. You can’t help but stare – kind of like when you see Aaron Neville’s mole on his eyebrow for the first time. I wanted to know what it was, what it did, and why other cameras don’t have it. It’s called a “plunger.” I think the name itself told the story of why no other camera had it – it was flushed away with this camera. In reality, it was a clever solution for the amateur photographer that needed a little speed. The plunger is a multi-tasker. When pushed down, it 1) advances the film, and 2) cocks the shutter. The photographer can leave the left index finger on the plunger and the right index finger on the trigger. After taking the shot, one rapidly pushes the plunger down and voila! You’re ready for another shot. I can fire off about two shots per second with this clever contraption. When you’re done shooting, simply close the front barn doors and press the plunger down until it stays. When you open it back up, the plunger shoots back up like an antenna.

For many folders before the 1960’s, the process of taking a picture was laborious. 1) Turn the knob on the camera body to advance the film. 2) Cock the shutter with a tiny lever on the front lens assembly. 3) Move your hand back to the camera body (or further forward to the front of the camera) to fire the shutter. This process alone might take 3-4 seconds for a practiced shooter. The Vitessa film advance/shutter cock plunger action took a fraction of a second. Of course, SLRs that would come out several years later accomplished the same task with a rapid advance lever. But I think we owe a bit of praise to the Vitessa engineers who solved a real problem with a quirky solution.

For many folders before the 1960’s, the process of taking a picture was laborious. 1) Turn the knob on the camera body to advance the film. 2) Cock the shutter with a tiny lever on the front lens assembly. 3) Move your hand back to the camera body (or further forward to the front of the camera) to fire the shutter. This process alone might take 3-4 seconds for a practiced shooter. The Vitessa film advance/shutter cock plunger action took a fraction of a second. Of course, SLRs that would come out several years later accomplished the same task with a rapid advance lever. But I think we owe a bit of praise to the Vitessa engineers who solved a real problem with a quirky solution.

Shooting with the Vitessa

Loading and unloading film. Loading requires a simple lift and turn of a lever on the bottom. The back/bottom comes off like many rangefinders from this era. The film loads opposite of most cameras with the canister on the right and the take up spool on the left. Turn the camera over and set the film counter wheel to the start arrow. When shooting, the counter is in a little window on the front of the camera. Thankfully, it advances up to count the frames shot. Many older cameras counted down, with some even refusing to shoot once they hit zero. You can also choose to set film type with a wheel inside the little frame counter window. Put the bottom back on, being sure to push while locking it back with the lever.

When you’re done with your roll, push the rewind release button on the bottom. The rewind crank is cleverly tucked away on the bottom. Pull it out, fold over the crank, and wind away.

Opening and closing the barn doors. Simply push the shutter button and the doors fly open, the lens board shoots forward, and the plunger ejects with a THWACK. This will make you jump the first time you do it. I suggest holding your finger over it so that it slowly ejects. This can also help keep parts from breaking with a camera this old.

Closing the camera is fairly easy. Pull the barn doors wide with two hands, push the lens board into the body with two fingers on either side (mind the lens!), and snap it shut. Finally, push the plunger down until it locks. It’s hard to describe in print, but doing it a few times will make you appreciate German engineering.

Setting the shutter and aperture. Now comes the frustrating part. Because they forced the LVS onto us (kind of like Apple forcing us into or out of hardware), the speed and aperture are interlocked. I find it easier (and backwards of how I think) to set the speed dial first, then grab the LVS tab on the bottom of the lens barrel to set the aperture. Yes, it sucks, but the alternative is to gorilla hold the LVS tab while turning the speed dial. You could always read your meter’s LVS and set that first, then slide the speed dial until you get the aperture you want. There’s something to be said about shooting “in the period” of a camera.

Focusing. The rangefinder is typical of folders, small and dim with the two viewfinders fairly close together. The focusing wheel on the back is fairly smooth, although my example wants to spring toward close focusing rather than free wheeling through the entire range. I don’t know if they are all like this or not. There is a nice depth-of-field scale along with a rotating feet gauge on the top cover. My rangefinder was out of adjustment, so I started researching how to do it. To my horror, most of what I found involved a complicated task of removing the top cover. But mine, thank God, only required removing the cold shoe to access the adjusting screws.

The lens. My example has the slower f3.5 lens than the top of the line f2 Ultron (which sounds like an alien saying, “We are from the planet Ultron that circles the star Crouton in the system Futon!”). It’s no slouch, though. It suffers from lens flare like many of the lenses from this era that had little to no coating. It helps to hold a hand up to the side of the lens or put a shade on while shooting.

Speeds. My example has speeds from 1 second to 1/500, plus Bulb. Unfortunately, the slower speeds are sluggish. Dripping naphtha into the shutter temporarily helps. One of these days I’ll pull the lens off and properly clean the shutter.

Curiosity. Every time I bring this camera along on a video shoot, it draws a crowd. A simple rangefinder or SLR gets a few raised eyebrows, but the Vitessa’s plunger is like a beacon. I haven’t met one person yet that has ever seen one of these cameras. My only other type of camera that gets this much attention is a TLR, but most people have seen one of those.

Quality. What can I say? It’s a Voigtländer. I haven’t met one I didn’t like. With a small format like 35mm, it’s important to have a sharp lens if you need enlargements. Cost vs. performance, I would compare this lens to the same era Zeiss-Ikons. A decade later, the Japanese cameras like Olympus and Canon would be giving the public the same quality of lens in their rangefinders. I occasionally shoot with a cheap consumer camera from this era, but they always leave me wanting more. They’re not bad enough to be interesting, and they’re good enough to pass. The Vitessa is both interesting and great.

“Fans of Racing” Winchester Farm, Lexington, KY

“CAT” Clark Farms, Lexington, KY

“Blue Grass Farm” Winchester Farm, Lexington, KY

“Tailspin” Lexington, KY

“The Parthenon Pant” Lexington, KY

“People’s Steeples” Georgetown, KY

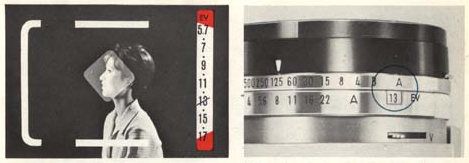

“Chicks” Clark Farms, Lexington, KY

Grandpa’s Purple Heart

Grandpa Keck’s Purple Heart from World War One.

Earl C. Kesterson, or Grandpa Keck, fought on the Western Front in the battle of Meuse-Argonne. It was the last great surge that eventually ended the war. Grandpa was severely injured from gunshot/shrapnel and mustard gas.

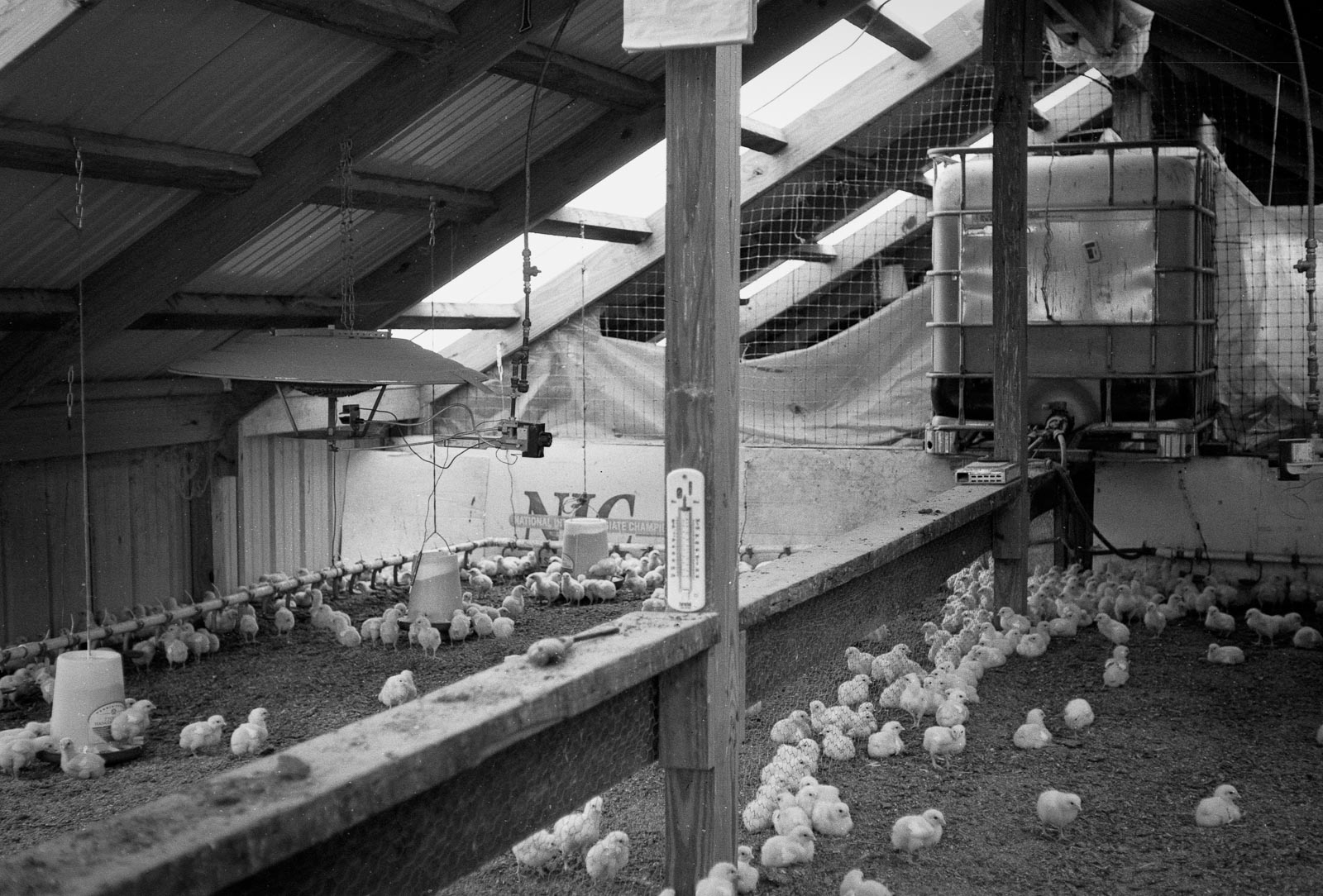

Grandma’s sister Bonnie (Aunt Dick) and Grandpa before shipping out to Europe

Mona (Grandma) and Clifford in South Point, Ohio

He spent several years in hospitals and was left with a near useless arm. All this with a new wife and baby at home in a little town on the Ohio River.

He’d only been on the front less than two weeks before the injury. I’ve often wondered about the hell he saw when he first arrived at the trenches – airships hovering, tanks running over soldiers, biplanes fighting and dropping bombs, smoke everywhere, trees uprooted – an utter human and ecological disaster. It was supposed to be the war to end all wars. Instead it was a spark.

Infantry medal given to WWI US soldiers

Grandpa Keck eventually came home and tried to pick up his life again. During the war, his Army paychecks kept getting stalled or lost. His former employer, Walter Johnson, advanced money to Grandma until the checks started to come in.

Grandpa (left) was a coal miner and fireman in the foothills of the Appalachians in southern Ohio before the war.

When Grandpa finally came back to Ohio after several years in hospitals, he needed to work. His old employer and friend Walter encouraged him to come on at the old mine again. Grandpa, having little use of one his arms, felt helpless. Grandpa used to shovel coal into the boilers as a fireman (“fireman” is often misused for “firefighter”). Walter told him he could drive a truck. Incredulously, Grandpa responded, “How?” Johnson got in a truck and tucked one arm behind himself, shifted the gear with his other while steadying the wheel with his knees, and drove off. Grandpa was now employed. His next son, my Dad, would be named Walter.

Baton Grandpa used as a court baillif. I’d hate to be on the other end of that lead ball.

Grandpa had several successful careers, most notably as a mechanic and court bailiff. He also was very active in several organizations, including the American Legion (one if its earliest members), the Masons, and the Elks.

He loved photography, inspiring my Dad to get a really nice Polaroid camera. He dressed in a coat and tie almost every day, even on the weekends. I don’t remember him, but family members say that he was well liked, cheerful, and loved by all. He never let that purple heart become a bruised heart. He also drove a standard shift the rest of life.

Family Camera

One of the main cameras used through the decades of the 40’s, 50’s and 60’s on my Dad’s side of the family. My grandfather later bought a giant Polaroid. He seemed to be one of the few to operate it, as he’s not in most of the pictures. An earlier family camera was the beautiful Kodak Bullet.

This is a Kodak Duoflex (1947-50). At first glance, it looks like a simple box or TLR camera. It’s actually a pseudo TLR (a modified box camera with a separate viewing mirror above the taking lens). Just like a box camera, you look down through a double-convex lens onto a mirror. (A TLR would have a matte focusing screen looking onto a mirror, through a viewing lens above the taking lens. The viewing lens would focus in parallel with the taking lens.) But this 620 camera has some unusual features for a snapshot camera.

- Tiplet lens

- adjustable f-stop from f8 to f16

- focusable lens from 3.5 feet to infinity, with distance markings

- automatic double-exposure prevention

- double-exposure override

- instant or bulb shutter speeds

- aluminum body

- attachable flashbulb bracket and reflector

The design is also quite beautiful. There are hints of art deco in the vertical ridges that run from the top onto the face, continuing to the bottom of the box. The ridges are continued on its plastic strap, making it appear continuous from bottom of camera to the neck. The top and bottom of the face are beautifully sloped. It reminds you of a late 40’s Hudson.

You can tell from the design, both aesthetically and technically, that Kodak was delivering a stylish camera to the post war consumers who wanted more control over their photography, but weren’t ready to spend a lot.

I cleaned up the camera and reassembled it. I shot one roll through it, but I must have misadjusted the focus scale on the lens. I’ll reset that, and maybe replace the pocked mirror before I take it back out.

Shot with a Nikon F2, Micro-Nikkor 105mm/f2.8, F Bellows, Kodak Portra 400

My First Photo

While cleaning up the basement this summer, I ran across some old negatives. Some of them were my Dad’s from the 1950’s and earlier. They reminded me that he was an excellent amateur photographer, and was thrilled to teach me the basics when I became interested. Dad’s prize camera was a 1954 Model 95a Polaroid. This was an expensive camera ($800 in today’s dollars) that Mom saved up for as a gift. We have many great family pictures taken with this camera.

My first pictures I ever took were with this camera when I was five or six-years old (see below). We were at my Grandma Keck’s house when I begged Dad to handle the camera. The camera was almost as big as I was. I hoisted it up, aimed it at my Dad’s concerned face, pressed the shutter, and waited for the picture to develop. It was blurry! Being the encouraging father he was, he carefully explained how to hold still before pressing the button. The next picture was perfect. I have that picture (see below) of my Dad’s concerned face accompanied by my sister on my wall. It’s still funny after all these years.

By the time I started to really get into photography as a teen, the film for the 95a (Type 42 – I don’t know why I still remember that) was phased out. I bought the last remaining roll at the drug store downtown and had a blast with it. Since then, this old camera has been a shelf queen.

For my first photo assignment as a freshman in high school, Dad unearthed his 1952 Ansco Viking folder camera. It was really a German-made Agfa Billy medium format camera that was scale focusing. My “assignment” was to take pictures of the high school football game. Not really understanding the disconnect between action photography and a 35-year-old folding bellows consumer snapshot camera, the night was almost a complete failure. The bellows had a light leak, the film was too slow, the light was too dim, my composition was well – more like decomposition. But I had fun!

My go-to camera at the time was a Kodak Instamatic-X, a 126 cartridge format snapshooter (see below). I can remember not understanding why my pictures wouldn’t come out like I envisioned them. But I kept shooting anyway. After my experience with the Ansco and the resurrection of the Polaroid, Mom and Dad could see I was becoming serious about this camera thing. For Christmas, they bought me a Minolta SRT-101 35mm SLR camera that I used until it fell apart in the late 90’s.

I shot for the school yearbook and newspaper, the local daily newspaper, and events through high school and early college. I almost chose photography as a career, but was offered a music scholarship in high school. That led to a career in audio and video production, which I don’t regret. Even though my profession allows me to express my creativity every day, it’s photography that allows my soul to speak.

My first (successful) picture. A concerned face and an unconcerned face.

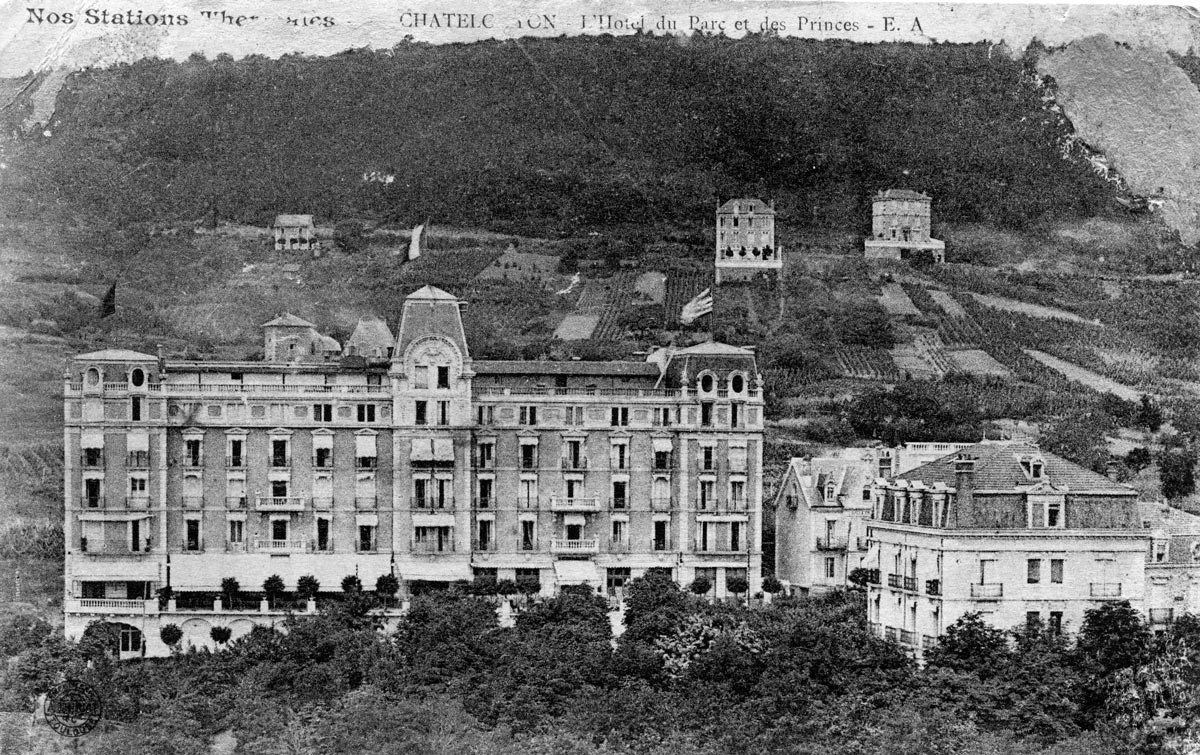

Postcard From France – A Mystery Revealed

An innocuous postcard among hundreds of old photos and documents. I kept shuffling it around from pile to pile as I was going through boxes and boxes of stuff from my recently passed aunt’s house. She was 92 when she died late last year. Her mother (my Grandma Keck) lived to be 95. My first task was to see if there were any important documents that would help our family lawyer piece together the value of her estate, partly because she left no will, and partly because she was…let’s just say extremely disorganized.

After we got the business end organized, it was time to go through photographs. Most of the ones I found I had never seen. They were either tucked away in Grandma’s room, or they were inherited by my aunt from an aunt and sister. Luckily my aunt had given me one of her aunt’s photo albums when she was alive. We carefully went through each photo as she identified who she could. This helped when I found the other hundreds of photos. But still, most were unmarked. There were also mementos from travels, clubs, and events. And then there was this beat up and faded post card. I almost threw it away several times. I guess the French caption made me curious enough to move it to another pile.

Each pile kept getting smaller and smaller until I picked it up one last time and studied it. My grandparents didn’t travel much, and I know they didn’t leave the country together. My great aunt did travel frequently, so it must be hers. But this was pretty old. I was guessing 1920’s, and she did most of her traveling in the 1950’s to 70’s.

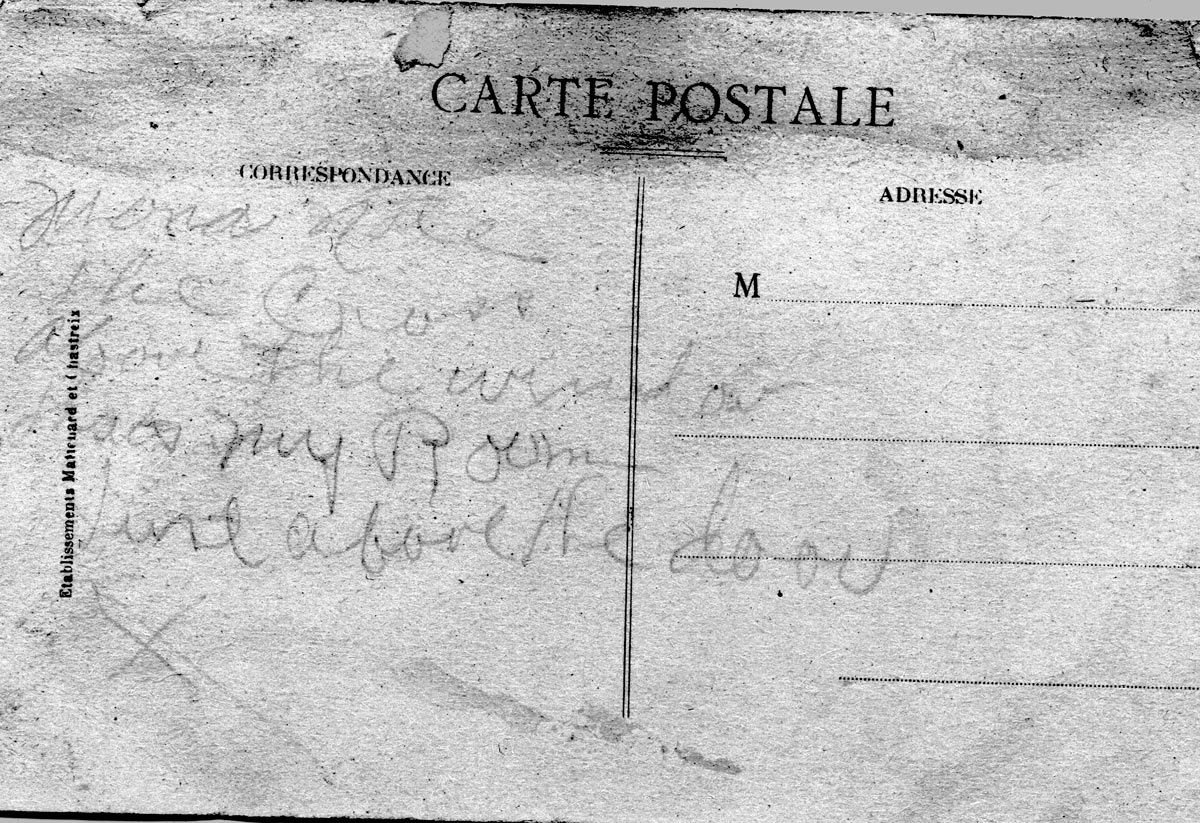

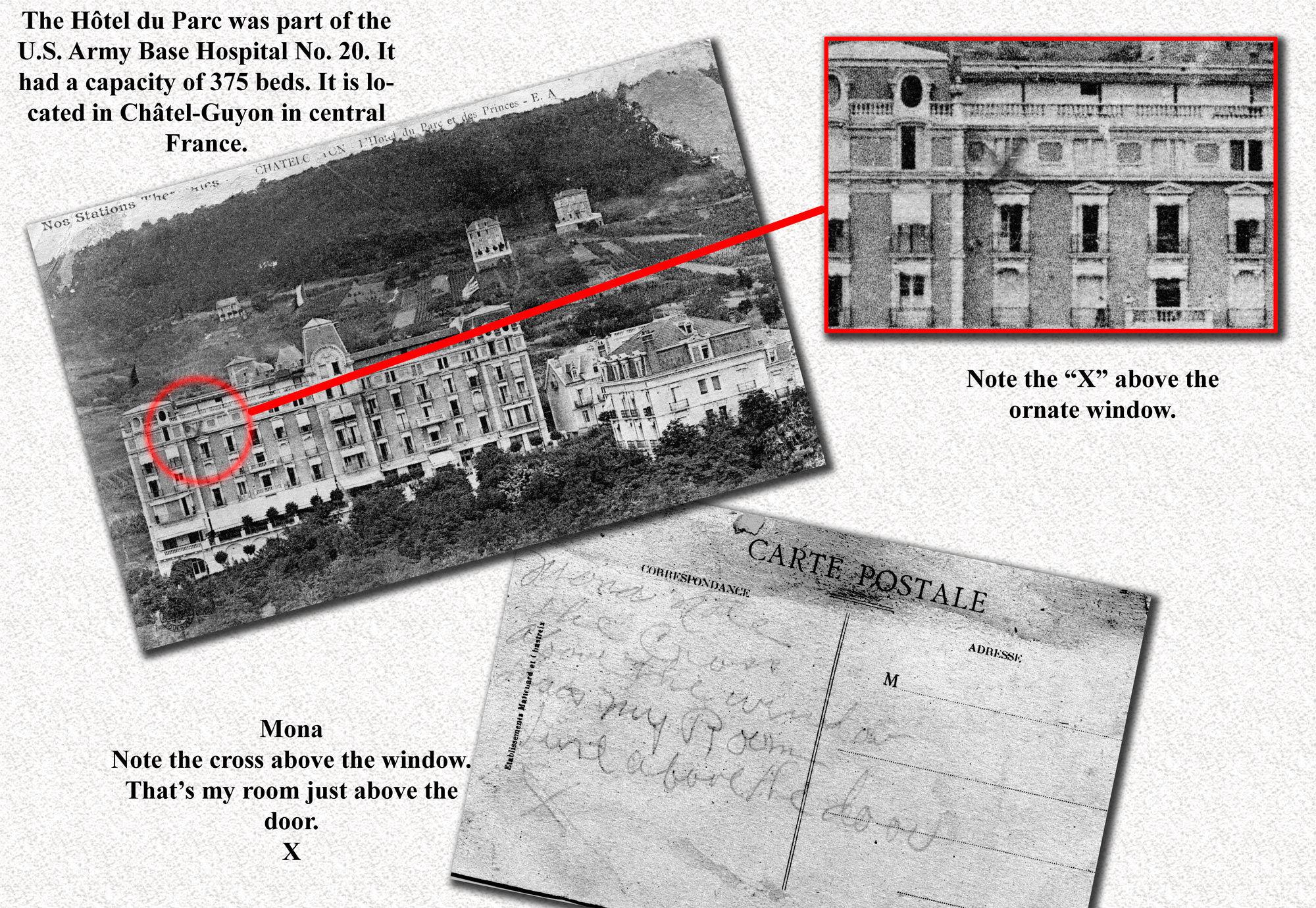

I put it under a bright light and put on my reading glasses. The picture was of a hotel somewhere in France. I turned it over to see who it was addressed to. No address, no postage. Why would this be saved? Then, as I turned it slightly, I saw faint impressions of hand writing on the back. It was written very poorly, like a child’s handwriting. All I could make out was something about “Mary (maybe)…cross…my room…door.”

Time for forensics. I used to do a lot of forensic audio when the police or a lawyer would bring me poorly recorded tapes from a sting operation or some other no-good deed. I would work for hours trying to hear what was being said (CSI and other unrealistic movies and shows have it wrong – it doesn’t magically take seconds to hear something in perfect clarity – it takes hours and days to barely hear something audible above the noise). You have to be careful to not hear something you want to hear, only what’s there. You can try to connect the dots (gaps), but its not always safe to assume. In this case, I was assuming a child wrote it.

In order to see the writing more clearly, I scanned it in grayscale and brought it into Photoshop. I used various tools to enhance the text, but I still couldn’t see much. When you’re working with forensic audio, it helps to go back to square one a few times. When you do, it forces you to go down an alternate path which might reveal something else. In this case, I rescanned the postcard, but this time in RGB color.

Playing with the color channels, I started reducing and increasing different colors. When I increased the blue channel, most of the text magically popped out. After blending some other channels in and sharpening the picture, I was satisfied I had revealed about all that was left.

I uploaded this image along with the postcard front to Flickr in an album I’d created for this giant archiving project. I’d hoped someone in the family could figure out who wrote it and what it meant. While visiting my mom, I showed her the pictures on my iPhone. As an writer and a lifelong word puzzle junkie, she was able to complete the words:

“Mona note the cross above the window. That’s my room just above the door. X”

Mona was my Grandma Keck’s name. I saw that earlier. What I had disregarded was the “X.” Mom said “X, find an ‘X’.” I flipped to the picture of the front of the postcard and zoomed in. I closely scanned back and forth until I saw it. There it was on the building itself in handwritten pencil. It finally dawned on us that my Grandpa Keck wrote this to his wife during World War 1. He was sent to the western front in France to battle the Germans. He was severely injured in the Battle of Meuse-Argonne on 9 Oct 1918. His arm was nearly shot off with a bullet or shrapnel. In addition, he was exposed to mustard gas.

After Grandpa Keck’s injury, he was shipped to a hospital in central France to recuperate. This is a postcard he sent Grandma showing where his room was. The Hotel de Parc in Chatel-Guyon (formerly Chatelguyon) was converted into a U.S. Army hospital. Obviously Grandpa was having great difficulty writing at the time, because his later writing samples were quite neat.

I have been able to track down Grandpa’s particular fighting unit (116th Infantry, 29th Div.) and where he was injured. It turns out that his unit was part of the final big push by the American and French forces into German lines that would ultimately end the war.

More about the U.S Army Post Hospital No. 20

Bourbon Barrel

Storage Below Ground

When you first see this structure at Waveland in Lexington, KY, it looks like the top of house on a hill. I’ve never been in this one, but it’s probably brick-lined like similar ones from this era.

Sunspot Chillin’

Onslow and Daisy. Onslow is a rescue from the Woodford Human Society. Although one of my requirements was that my new cat would be okay around dogs, I was afraid he would be scared of Daisy. When I brought him home and let him out of the carrier, he immediately went up to Daisy and rubbed on her, purring. Well that was settled right away.

Daisy was a little taken aback with his forwardness. It had been a while since she was around a cat that showed any affection toward her (my other cat just hates life and everyone in it). Now, they greet each other, hang out together, and even sleep together at night.